Q5(c) Central Business District (CBDs) are in decline as the economic core of metropolitan cities. Critically examine. 10 Marks (PYQ/2024)

Answer:

Introduction

Central Business Districts have long been seen as the heart of metropolitan economic activity. Traditional urban theories, such as Burgess’s Concentric Zone Model and Central Place Theory, positioned CBDs as natural hubs due to agglomeration economies and high accessibility. However, recent trends—ranging from decentralization, rising costs, and technological shifts to flexible work—have challenged the CBD’s historical role, prompting debate on whether they are truly in decline as epicenters of urban economic power.

Historical Role and Traditional Advantages

- Agglomeration Economies and Accessibility: Early positivist research in urban geography, using quantitative methods, emphasized the benefits of spatial concentration. The proximity among firms and institutions in the CBD reduced transportation costs and promoted knowledge spillovers.

- Concentric Zone and Central Place Theories: Models like the Concentric Zone Model (Burgess) and Central Place Theory justified the dense layout of businesses in the CBD as a natural consequence of urban growth and market demand. These theories suggested that the CBD’s high accessibility and concentration of services created economic synergies.

Factors Contributing to the Perceived Decline

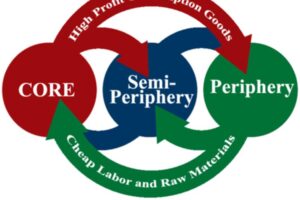

- Decentralization and Polycentricity: The Multiple Nuclei Model (Harris and Ullman) argues that modern cities evolve into polycentric networks where numerous sub-centers emerge. With improved transportation and communication, many companies now establish offices in suburban business parks or “edge cities” to take advantage of lower rents and better space.

- High Costs and Urban Congestion: According to Bid Rent Theory, as land prices in the CBD escalate due to demand, certain industries begin relocating to areas with lower costs. High rents, congestion, and limited parking further diminish the attractiveness of central locations for some businesses.

- Technological Shifts and Remote Work: The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of telecommuting and flexible work arrangements. With digital communication reducing the need for physical proximity, companies and professionals are questioning whether maintaining large, centralized office spaces is always economically justified. Declining occupancy rates in cities such as New York and London underscore this trend.

- Environmental and Quality-of-Life Considerations: The increasing emphasis on sustainable urbanism and liveable cities has led policymakers and residents to favor decentralization. The push toward green spaces and reduced pollution sometimes conflicts with the traditional density and high-traffic conditions of CBDs.

Empirical Examples and Data

- New York City: Recent reports indicate that Manhattan’s office occupancy fell significantly post-pandemic, as businesses downsized or shifted to hybrid models. Economic studies report substantial decreases in leased office space—signalling reduced demand for traditional CBD environments.

- London: Similar observations from London reveal that while the City continues to host high-value financial services, there has been a noticeable dispersion of business activity to suburban areas, driven by rising lease costs and evolving workplace practices.

Bridging Theories: Positivism vs. Behavioral and Integrative Approaches

- Positivist Tradition: Early geographic positivism provided rigorous, quantitative evidence for the benefits of a tightly clustered CBD. However, while valuable, these methods often overlooked subjective experiences and evolving consumer preferences.

- Behavioral and Integrative Approaches: Modern frameworks incorporate behavioral insights—such as the role of individual perceptions, strategic corporate decisions, and social priorities—in explaining the shift towards decentralization. The integration of these approaches has fostered a more holistic understanding of urban dynamics.

- Globalization and Network Theories: The work of theorists like Anthony Giddens and Manuel Castells points to the impact of globalization and digital networks on altering spatial patterns; businesses can now operate effectively over long distances, reducing the inherent advantages once held exclusively by CBDs.

Conclusion

While CBDs have historically served as the vibrant economic cores of metropolitan cities, a multiplicity of factors is reshaping their role. Decentralization, high operating costs, technological advancements, and evolving lifestyles are contributing to the dispersion of business activities beyond traditional centers. Although the CBD remains vital for certain sectors—especially those dependent on face-to-face interactions—the evolving urban landscape suggests a shift towards a more polycentric metropolitan model. A balanced perspective acknowledges both the enduring strengths of centralized hubs and the emerging need for adaptive, decentralized approaches to contemporary urban economic development.

5(d) There is a need for gender-sensitive regional development. Elaborate. 10 Marks (PYQ/2024)

Answer:

Introduction

Gender‐sensitive regional development refers to the integration of gender perspectives into the planning, design, and implementation of regional policies and projects. This approach recognizes that development is not gender neutral and that both men and women experience economic opportunities, social services, and environmental resources differently. By addressing these differences, gender‐sensitive policies can foster more equitable and sustainable regional growth.

Rationale and Importance

- Social Equity and Inclusive Growth: Traditional regional development models often overlook the roles, challenges, and contributions of women, thus perpetuating gender inequality. Women, who constitute a significant segment of the informal economy and agricultural labor, frequently have limited access to resources and decision-making power. Addressing these disparities helps ensure that the benefits of regional development are shared equitably.

- Economic Efficiency: Empirical research indicates that empowering women economically—through increased access to credit, education, and employment opportunities—can boost overall regional productivity. Some studies suggest that narrowing the gender gap could potentially raise GDP by billions, contributing significantly to national prosperity.

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) are interlinked with other goals such as SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 8 (Decent Work). A gender‐sensitive approach directly supports these global targets by ensuring that regional development policies promote both economic growth and social justice.

Theoretical Frameworks and Models

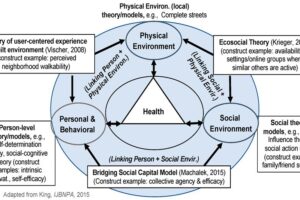

- Gender Mainstreaming: Developed by United Nations agencies in the 1990s, gender mainstreaming is the systematic integration of gender perspectives into all stages of policy and planning. This approach recognizes that gender is a cross-cutting issue affecting all aspects of development.

- Feminist Political Ecology: Theorists such as Doreen Massey and Nancy Fraser have argued that social power relations shape the distribution of environmental benefits and burdens. In regional development, understanding these dynamics ensures that environmental and economic policies do not exacerbate gender disparities.

- Intersectionality: Building on Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work, intersecting social identities—such as gender, class, ethnicity, and age—must be considered in regional planning. This perspective ensures that policies address the needs of diverse groups rather than favoring a homogeneous “ideal citizen.”

- Common-Pool Resource Theory (Ostrom): Elinor Ostrom’s principles on managing shared resources apply to regional development by emphasizing that effective governance requires inclusive participation. In gender-sensitive development, this means ensuring that both women and men are involved in managing natural and economic resources.

Policy Implications and Examples

- Gender Budgeting: Governments can allocate resources specifically for women’s development, ensuring that public investments in infrastructure, education, and healthcare reflect the needs of all citizens.

- Land and Resource Rights: Secure land tenure and access to credit for women are critical. For example, in parts of India and Africa, initiatives that empower women through land rights have resulted in improved agricultural productivity and stronger community resilience.

- Capacity Building: Training programs for women entrepreneurs and local leaders enable more robust participation in regional economic activities. In Scandinavia, for instance, gender‐inclusive urban policies have led to innovative solutions in the provision of childcare and public transport, supporting both work and family life.

Case Studies

- Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in India: In India’s rural regions, SHGs have empowered thousands of women by providing microcredit, training, and social support. These groups have not only improved women’s livelihoods but have also contributed to local economic development and better resource management.

- Southern African Development Community (SADC) Initiatives: Several SADC countries have implemented policies to integrate gender perspectives into regional water resource management. By involving women in decision-making and adopting gender-sensitive practices, these initiatives have helped reduce conflicts over water use and enhance community well-being.

Conclusion

A gender-sensitive approach to regional development is essential for achieving a more equitable, sustainable, and resilient future. By incorporating mainstream frameworks such as gender mainstreaming, feminist political ecology, and intersectionality, policymakers can transform traditional models into inclusive strategies that acknowledge and leverage the diverse contributions of all citizens. This, in turn, enables regions to harness the full potential of human capital and ensures that development benefits are distributed equitably across society.